- Home

- Bannie McPartlin

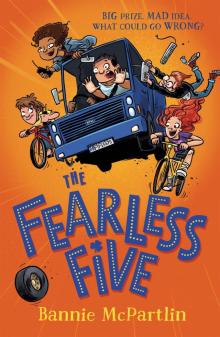

The Fearless Five

The Fearless Five Read online

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

The Five

1. The Match

2. The Knockout

3. The Family

4. The Idea

5. The Den

6. The Plan

7. The Key

8. The Band

9. The Pepper Spray

10. The Public Poo

11. The Bribe

12. The Runs

13. The Escape

14. The Rehearsal

15. The Lies

16. The Photo

17. The Robbery

18. The Getaway

19. The Gurriers

20. The Mastermind

21. The Hummingbird

22. The Fear

23. The Question

24. The Hiccup

25. The Wait

26. The Chase

27. The Panic

28. The Match

29. The Gig

30. The Guards

31. The Money

32. The Ticket

33. The Train

34. The Town

35. The Farm

36. The Animals

37. The Meal

38. The Work

39. The Beach

40. The Hero

41. The Fight

42. The Secret

43. The Truth

44. The Fall

45. The Traitor

46. The Station

47. The Package

48. The Confession

49. The Interview

50. The Caution

51. The Future

Footnotes

About the Author

Copyright

To my chief advisor, Laura Kerins (aged 12),

your honesty (sometimes harsh) and insight

(always hilarious) were AWESOME.

Bannie loves you.

To all the kids who rock my world,

Bannie loves you.

THREE THINGS YOU SHOULD KNOW

Some people like to know more than others. I have a lot of story to tell, so to make sure that some of you don’t get bored I’m going to add some extra things in the ‘Three Things You Should Know’ sections at the bottom of the page.

For example:

My cat would bite me to get at my chips.

He liked to chase cars.

He died under the wheel of a Ford Cortina with a mouth full of chips. RIP Mittens.

These are things you don’t need to know but I think you should. It’s your choice. You decide …

The Five

This is the photograph that hit the national news and made five kids the most wanted kids in Ireland.

From left to right: Sumo Lane, Walker Brown, Charlie Eastman, Johnny J and Jeremy Finn.

It’s framed on my mam’s wall over her prized white marble fireplace and next to my sister Rachel’s nursing diploma and my brother Rich’s gold record. The picture features my four friends and me, dressed head to toe in green, white and gold, our faces painted with shamrocks and harps and all of us grinning fiercely. We look nuts. We were nuts. We just didn’t know it.

On the far left is Sumo Lane.

Sumo’s real name is Brian, but he was never a Brian. Brians are mostly brainy and sometimes boring. He was neither of those. Sumo is huge. At twelve years old he’s six foot tall and wider than a cottage door.

People moved out of the way when Sumo walked down the street. I came up with the name Sumo when we met, aged six, because even though he wasn’t six foot then, he had jet-black hair, pudgy cheeks and he was always the biggest kid in the room. The name just stuck. Kids, teachers, parents (even his own) called Brian ‘Sumo’.fn1

This is Sumo’s best friend, Walker Brown. As you can see, he’s skinny and tiny. He’s thirteen in this photo, but he could pass for an eight-year-old.

We all wore Irish-flag-coloured, furry top hats, but Walker wore his reluctantly because he was serious about his hair. He kept the sides of his hair short and the top long. He backcombed it so that it sat like a giant slick wave on top of his head and it was so full of hairspray that it didn’t move. A lot of effort went into Walker’s hair, but it added almost two inches to his height so it was worth it. His big, thick, horn-rimmed glasses were so heavy he was always holding them against the bridge of his nose so that they didn’t fall off. He had asthma, which meant he spent a lot of his time wheezing and sucking on an inhaler, so I used to joke that he was called Walker because he definitely wasn’t a runner.fn2 That always got a laugh. He’s the only one not pretending to smile for the camera. He said we were crazy and that we’d get caught. He was right.

Twelve-year-old Charlie Eastman stands in the middle and just in front of us. She looks like the leader of the gang here and (sometimes) she was, even though I didn’t like it one bit!

The green Ireland shorts Charlie is wearing are so long on her they look more like baggy trousers, which wasn’t something I noticed back then. Her skinny elbows point outwards as she rests her hands on her hips. That’s what she did when she wanted anyone to know she meant business. She’s winking under that big tall hat and that’s her own red, wild and curly hair that goes halfway down her back. She painted her lips green to match the large shamrocks on each cheek. I didn’t want her there that day. She was new to our gang and she’d bribed her way in, but the truth is, for what we were about to do (and it was seriously dangerous), we needed her.fn3

Beside Charlie, and with another mop of wild curls, is my very best friend in the world, Johnny J Tulsi. Thirteen-and-a-half-year-old Johnny J is the oldest of us. Everyone loves Johnny J, even adults. He’s just cool.

Johnny J didn’t really look like the rest of us, who were pale-skinned, red-cheeked, pockmarked and freckled. He had smooth caramel skin, his father’s brown eyes and mad curly hair, except his was light brown like his mother’s.fn4

My mam always called him handsome and offered to feed him every time she saw him. Charlie followed him around like a shadow and giggled every time he spoke, even when he wasn’t funny. (Charlie didn’t find me funny at all, and I was officially the joker of the group.)

Johnny J always laughed at my jokes. We had the greatest conversations ever shared between two boys under the age of fourteen, and when I was scared or sad or nervous, he always knew what to say to make me feel better. We knew each other better than anyone else in the world and we told each other everything.

He’s smiling in that photo even though his whole world was falling apart. I really admired him for that. Johnny J was really brave. He was an only child and his father died in a car crash when he was only two years old, so when his mam got sick it was a real worry, but he never complained. Even when things got really bad and he knew his mam was dying. He never asked for help, but what kind of friends would we be if we didn’t offer?

So this is me, Jeremy Finn, thirteen years and two weeks old, next to my best friend, with my thumbs high in the air and a big cheesy grin, pretending I had everything under control. (I didn’t.) Spoiler alert: This does not end well.

And yes, I used to wear my brown hair to my shoulders (like a girl!), but I’d always worn it that way (I hated change and my mam thought it made me an individual).fn5 Even with the wonky shamrocks my freckles are big enough to be seen. And you can’t tell from the picture, but I’d had the runs for a week and I’d thrown up at least twice.

The headline in that newspaper clip screams ‘Have You Seen the Fearless Five?’ We had no idea what we were up against. We were foolish and we could have really messed our lives up, but we tried our best. That’s what I think when I look at the faded old news clipping framed above my mam’s prized white marble fireplace, next to my sister Rachel’s

nursing diploma and my brother Rich’s gold record. We tried … And we made a really big mess … And it was the saddest, scariest, weirdest, time in my life, but it was also the best fun I ever had.

And it started here …

1

The Match

It was 13 June 1990 and a game of football played in Italy between two foreign nations in the World Cup was a turning point for us, not just for my best friends and me but for the whole country of Ireland. We needed the Soviet Union to lose to Argentina. The Soviet Union’s loss was Ireland’s gain, and we advanced to the knockout stage of the World Cup and it was A VERY BIG DEAL. We were high on life, my friends and me. Anything seemed possible. I guess that’s how the whole thing started.

So there we were, in the park, getting ready for a boxing match. We had just finished our very last day of primary school and we were looking forward to a whole summer of fun before heading off to our new secondary schools in September. Kids were everywhere and everyone was buzzing, still singing football chants and talking excitedly about football and how Ireland was IN THE WORLD CUP!

Johnny J was jumping up and down on the spot, his corkscrew curls bouncing in my face as I tried to glove him up. He was about to box against a boy called Fitzer. He was a right bruiser, bigger than Johnny J and a bully. He had a deep voice, greasy hair that just kind of dripped from his head and a faint dark moustache that stopped halfway across his top lip and just looked weird. Freaky Fitzer fancied himself as fast, strong and tough as nails.fn1 Of all the lads who agreed to fight Johnny J, I figured he’d be the easiest to beat.

We charged one pound per kid to watch the fight, and one hundred and twenty-five kids turned up. Once we’d paid Fitzer the tenner we’d promised him and bought him a Mars bar (which we’d also promised him), our profit was one hundred and fourteen pounds and fifty-one pence, whether our boy won or lost. It was a good thing too because Johnny J was no fighter. He just really needed the money for his mam.

Nobody named it back then, but we all knew that Mrs Tulsi had been battling cancer for a few years. It was obvious she wasn’t getting any better. Johnny J was desperate. It was Walker who first mentioned that if she lived in America she’d be fine. The Americans were really medically advanced. At least that’s what he said, and because he had won Young Scientist of the Year for his older sister Aprilfn2 and he was the only person we knew with a computer, we believed him.

‘Mrs Tulsi needs to go to America. Fact,’ he said. He convinced us that all we had to do was buy Mrs Tulsi a plane ticket and taxi fare and she could just walk into any hospital in America and they would welcome her in and fix her up in no time at all. Without the benefit of Google we believed him. We were naive, but if we didn’t believe Walker, then what? Mrs Tulsi couldn’t die! Johnny J left in this world with no parents at all?! Nah, I wasn’t having that. We were going to save her. We were going to save him. FACT!

I spent a lot of time worrying about Johnny J and his mam and his poor Uncle Ted, his dead father’s brother. Uncle Ted was a really nice man who was always there for Johnny J and his mother. Every time he saw me he winked and told me I was a good kid, which was nice. No one else in my life did that. Uncle Ted was browner than Johnny J and had dark curly hair and wore cool clothes, like leather trousers and T-shirts with rock bands on them. He played the guitar and taught Johnny J to play when he was little. Johnny J said he could have been a rock star but he gave up music to take over running the family garage after Johnny J’s father died. When Uncle Ted walked, he had a bounce to his step. I spent a lot of my early years trying to walk like Ted Tulsi, but it never happened. I just wasn’t cool enough.

After Walker told us about America I’d lie awake in my bed thinking about all the things I could and couldn’t do to raise money. Sometimes all that thinking made my stomach hurt. I was cursed with a nervous stomach. My mam said I took after my dad’s mother, Nanna Finn, who spent so much time in her toilet she had a bookshelf and plants and pruning shears in there. It was during one marathon cramp-fuelled thinking toilet session that I came up with the idea to start the boxing matches for money. Flights to America were really expensive back then, over a thousand pounds. That’s a lot of fights for a boy who didn’t really like to fight, but it was the only idea I had.

So there we were in the park. Freaky Fitzer and Johnny J danced and bounced around for a bit. Some of the crowd cheered. Some jeered.

‘Go on, Johnny J. You can do it.’

‘Smash his face in, Fitzer.’

‘Get a move on, grannies.’

‘Punch each other, muppets!’

The ring was just an area marked out by four coats, one in each corner. Sumo stood on guard, with his massive arms crossed and his legs spread wide apart and his chest sticking out. He looked like the bouncer who stood outside Barry’s Betting Shop. It was Sumo’s job to make sure the audience didn’t push into the ring, and he took it seriously.

‘All right, fellas, calm it down. Come on now. Give the fighters some space.’

Everyone shuffled back, and Sumo nodded to himself and took out a Spam sandwich from his pocket, dusted it for fluff and demolished it in two bites. Walker sat at the picnic table, holding his big glasses against his face with one hand and counting out the money with the other. I stood in Johnny J’s corner, hoping he wouldn’t get killed, shouting words of encouragement while he bounced about on his tippy-toes. He bobbed and weaved and tired himself out before one punch was even thrown. I heard Charlie before I saw her. She was shouting down from somewhere in the sky.

‘Keep your hands up. Come on, Johnny J, stop dancing, start hitting.’

It was my job to say encouraging stuff. Annoying! I looked up and there she was, sitting like Marvel Comic’s Black Widow, spying on everyone with her flaming-red hair in two bunches either side of her head and her eyes flashing down at me from the highest tree. Show-off! Hollering away, Oh look at me. I’m a girl and I can climb a tree! Big deal. Not helpful at all. I was sick she was there because lately she was everywhere. Like a bad smell, she lingered and was hard to get rid of. I tried to nickname her Bad Smell but it didn’t catch on the way Sumo or Freaky Fitzer had. Disappointing.

It was while Charlie was distracting Johnny J with her unhelpful comments that Freaky Fitzer let fly with his first punch. His right fist connected with Johnny J’s left eye and it was game over as Johnny J hit the deck. Freaky Fitzer grabbed his tenner and Mars bar and was out of there before Sumo got Johnny J to his feet. The fight was over before it had begun.

2

The Knockout

In the aftermath of the quickest fight in history it became obvious from the loud booing and hissing sounds that the crowd felt they hadn’t got value for money. I shouted to Sumo to escort Walker and the money away from the angry mob to a meeting point deeper in the wooded area of the park. Then placed myself between a dazed Johnny J and a bunch of mean schoolkids, trying to calm everyone down by assuring them that the next fight would be better.

‘So who’s fighting next?’ someone shouted.

‘Sumo,’ I said, but I was lying. Sumo would never fight. He didn’t believe in it. He said it hurt God or something. He could be a bit of a holy roller. (That’s what my dad called people who went to Mass every day and judged people who didn’t.)

There was a hush. ‘Who’d fight Sumo?’ a boy in the crowd said.

‘Ah no,’ another kid said. ‘Sure he’s got hands the size of frying pans!’

‘Well, who’s brave enough?’ I said.

Every kid there looked the boy beside him up and down. No one spoke up. No one was brave enough.

‘Tell your friends. The prize is twenty-five quid,’ I shouted. There was a collective gasp. Twenty-five quid was a lot of money. They all moved off chattering among themselves and the terrible fight was forgotten.

Charlie climbed down from her tree. ‘Nice one,’ she said.

‘Go away,’ I said.

Charlie grabbed her bike. She was always on her pink

Triumph 20. It was like it was attached to her. Johnny J was sitting on the grass, still slightly dazed.

‘You OK?’ she asked him.

‘Yeah, grand.’

‘I brought some frozen peas, in my basket. If you want to take some of the swelling down.’

‘Ah yeah, cool. Thanks,’ he said, and he placed the bag of peas on his eye. Johnny J was always polite to her, which really got under my skin. I helped him to his feet and we walked on. She cycled by his side.

‘We’re trying to do a little business here,’ I said, hoping she’d go home.

‘I know. I want to help.’

‘Well, you can’t.’

‘I can fight,’ she said.

Johnny J and I both laughed.

‘Seriously. I beat up my brothers all the time. My dad said if I was a boy I’d be the next Barry McGuigan.’fn1 Johnny J and I laughed again. Charlie Eastman really was the vainest person I’d ever met.

‘You’re not fighting,’ Johnny J said.

‘Don’t know what you’re laughing at. I’d win.’

‘Against Sumo?’ I said, and laughed.

‘He’d just stand there, so of course I’d win, but I’d do some fancy moves to entertain the crowd,’ she said, and she took her hands off the handlebars and started air-boxing as she cycled.

Johnny J laughed again, but this time it was with her not at her so I didn’t join in.

‘No girls fighting,’ I said.

‘Who says?’

‘I say.’

‘Johnny J?’ she said, looking to him to stand up for her against me, as though that was even possible!

‘He’s right. Sorry,’ he said.

‘No one will pay to see girls fight,’ I said. She stared at Johnny J, again waiting for him to back her up. He didn’t.

‘He’s right. I’m sorry,’ he said, and I wished he’d stop apologising.

She was hurt. ‘Girls can fight. Girls can do anything,’ she said, and it looked like she was about to cry. (Crying is another reason I really hated hanging with girls.)

The Fearless Five

The Fearless Five